On the southern half of the Pyrenees in Spain and Andorra there is a series of Romanesque churches clustered tightly with a rather interesting interconnecting iconographical thread unique to the region.

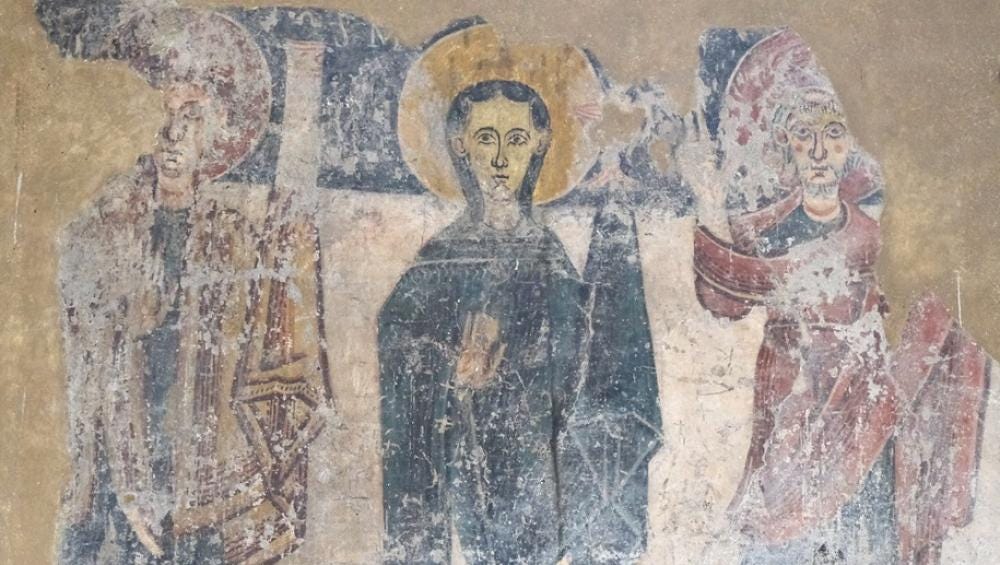

All of these churches include a depiction of the Virgin Mary, often behind the altar in the apse, holding a chalice that varies in stylization in each iteration. Before I discuss further I’ll reproduce them below, with the dates referring to the best guess I could find about when the icons were made, not when the church was built. I will keep the names in Catalonian.

There are many interesting things about these Romanesque Churches, but for our study I want to focus on the ubiquity of the Virgin holding a chalice. (And I guess I first need to say that the people out there saying it’s actually a lamp are just wrong. Maybe a few of the instances can look that way, but looking at them all there’s no way.) There aren’t many examples in Western art of the Mother of God holding a chalice, and to find so many examples cloistered together within about a 100 year range is unique, to say the least.

In all but one of these depiction she is holding the chalice with her robe, a common iconographical trope used in relation with the Eucharist and other holy objects because of the danger they posses to those who touch them with bare hands. Only in the last image is she holding it with her bare hand, but this one is already a bit out of the usual since it’s part of a larger scene of the Ascension. My theory here is that the cup is empty and signifies the Church, almost always inextricably linked with the Mother of God, waiting for the Holy Spirit to descend upon the Church (Mary). Touching it with her bare hands shows that Pentecost has not yet come, but we see her holding it up to show the anticipation of it being filled up.

Why exactly this image shows up so frequently in the Southern Pyrenees between 1100-1200, we don’t exactly know. We also can’t say for sure why this depiction doesn’t spread elsewhere. The closest example I could find is a stained glass Crucifixion at the Sens Cathedral where a woman, presumably Christ’s mother, is at his side collecting His blood in a chalice, with her bare hand. It would’ve been made around the 13th century, so solidly after these Churches had finished their depictions. Not saying there isn’t a direct connection, but if there is an artistic connection it would be interesting that a Gothic cathedral using stained glass found inspiration in Romanesque frescos. If there are more example that you know of please let me know!

The historian Joesph Goering poses the following theory about these icons:

A third possibility, even more compelling to my mind, is that the image of this holy vessel did indeed spread, and very widely, but in a form that could easily lead to misunderstanding. When the vessel— the holy grail—was quite literally cut loose from the Virgin and stripped, as it were, from the bosom of the Church and the Apostles, it was free to become the Holy Grail of medieval courtly romance. As the sacred vessel came to be associated in song and story with Perceval (and Lancelot and Galahad) rather than with Peter and Paul and the Virgin Mary, it left the realm of sacred history and entered that of romantic fiction. (Pg. 138, The Virgin and the Grail, Yale University Press, 2005)

I think Goering is onto something here, and his book The Virgin and the Grail is a fascinating read on the subject of the history of the Holy Grail, something which I’ve written about with the story of Perceval which is the first story (that we have) to introduce the Arthurian Grail narrative.

What gives Goering’s story further credence is that in the story of Perceval, written by Chretien de Troyes in the late 1100’s, the first and only time we see the grail is in the context of it being held by a virgin girl in what I argued in my post is a liturgical procession influenced by the Great Entrance. If I’m correct then a hurdle we have to overcome is why a female is engaged in an activity normally reserved for priests, however if we understand Chretien’s poem in light of the Catalonian Icons then it begins to make sense since Chretien may well be tapping into the imagery directly or through second hand accounts. I should also note, there are icons of Mary, such as in Ravenna in in the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo where the Holy Virgin is wearing a chasuble, liturgical vestments, from the early 1100’s. So the idea of the Mother of God playing a liturgical, not in the way female ordainationists think, does exist.

But that’s not all. The word “grail” etymologically seems to come from either Southern France or Northern Spain, as one academic says, “the first documentary references to the word come from the Pyrenees region, specifically in its Catalan-speaking area.” And going into the world of hagiography, the mountains of northern Spain is precisely where the Cup of the Last Supper was said to be sent by St Lawrence, who was in charge of many relics including the Holy Grail, for safe keeping.

So in the area where St. Lawrence is said to have sent the Holy Grail for safe keeping, we have a unique artistic proliferation of depictions of the Virgin Mary holding a Eucharistic chalice. This is also the same place where the word grail is first used and shortly thereafter Chretien’s poem appears describing the Grail, which we’re explicitly told contains a eucharistic host, held by a virgin woman. Is this a series of huge coincidences? Perhaps, but I’m not inclined to think so.